When poet Crystal Wilkinson became a mother, she knew that her children would love her grandmother’s biscuits. However, when she first made them, they didn’t turn out as planned. Turns out, Wilkinson had been trying hard to recreate her grandmother’s biscuits, but could not emulate the exact taste because her grandmother had never written down the recipe.

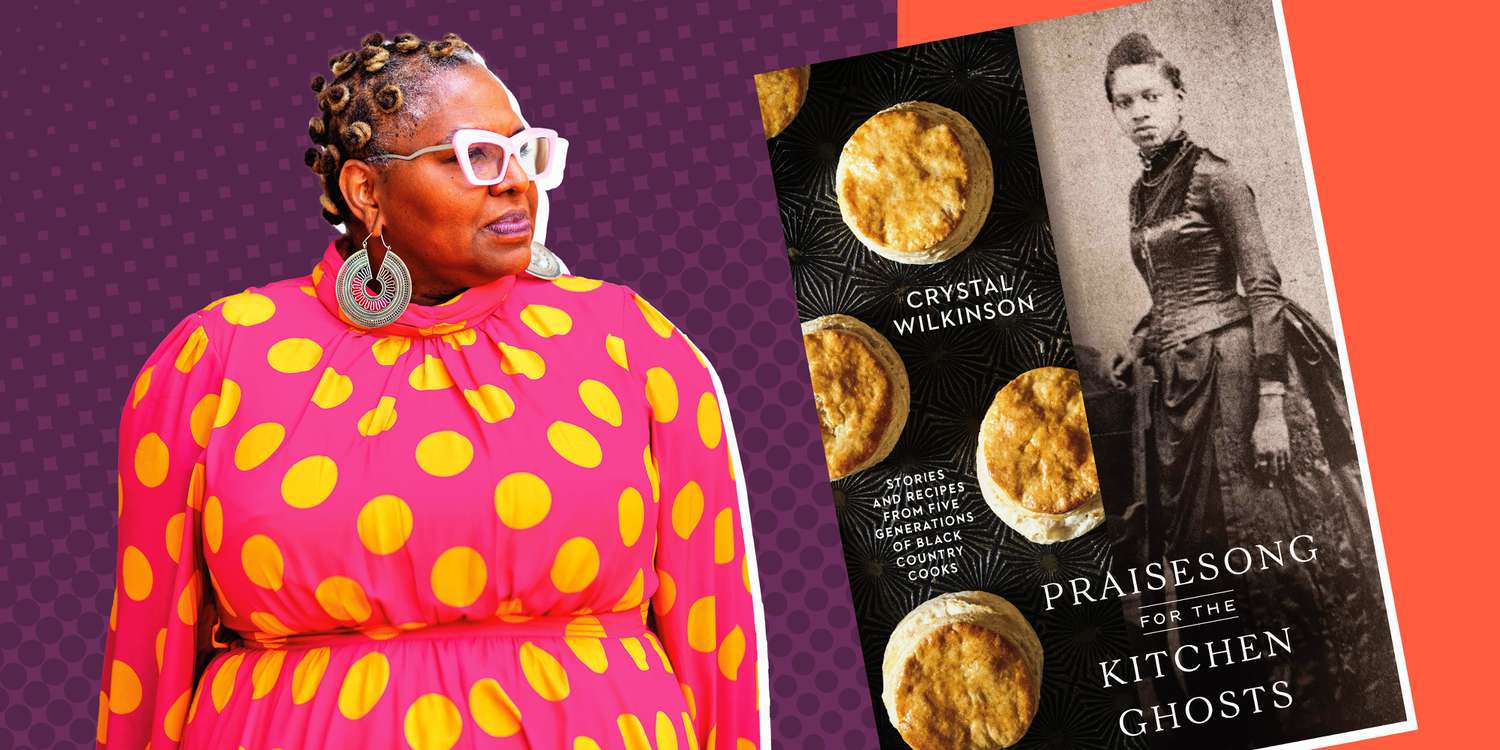

In Wilkinson’s new culinary memoir, Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks, the author, professor, and former Poet Laureate of Kentucky traces her family’s roots through Appalachian foodways.

Kelly Marshall

The history of Black Appalachia, or Affrilachia—a term coined by Black Appalachian poet Frank X Walker—has been vastly undertold, Wilkinson says. However, African American life in this region, which stretches across the Appalachian Mountains in 13 states, can directly be tied to many contributions to America’s food history. The unique ways in which Affrilachians gathered, prepared, and cooked food is a necessity in the canon of American cuisine.

“The areas in Kentucky where my family is from are not considered Southern because of the harsh winter weather,” says Wilkinson. “Canning, smoking, and burying potatoes was for the sake of survival. Everyone knew that the winter was going to be rough, so there needed to be enough cured meats and vegetables in order to feed entire families. Our ancestors did a lot of hard work to make sure you live through the winter.”

In writing the book, Wilkinson says she learned a great deal about her culinary matriarchs, and discovered how more than 200 years of cooking is still present in the dishes she makes for her own family and community.

She stresses that Affrilachian recipes and the storytelling around those cooking traditions supports larger conversations about the wide spectrum of African American foodways. “The way Black Southerners fix greens might be different from the way folks cook them in the North or the Midwest…we are not monoliths,” says Wilkinson.

Kelly Marshall

While researching family culinary history, Wilkinson also learned how important it is to understand that as time passes, resources and access to cooking tools vary from family to family and evolve even within families.

“As my book was being edited, one of the food testers called and said that although she followed the directions, she burned the Granny Christine’s Jam Cake. I was not surprised by this one bit. It’s not 1968 for one. And there are many things that my grandmother didn’t have, including a state-of-the-art oven.”

Wilkinson solved the food tester’s dilemma quickly. The cake was burned because the original recipe had a cook time of four hours. At that point, Wilkinson realized that she would have to leave room for the reader–advice that she often shares with her creative writing students at the University of Kentucky.

“You have to test each recipe more than once. Reinterpret what a dab is, or even a touch. It can be a science, but it’s also cultural, intuitive, and spiritual,” she says. “You’ve got to leave room for the ancestors and how you can be innovative in bringing a particular, and older, recipe into 2024. You’ve got to leave room for your palates, too! This can be about how the food is cooked or its nutrition. For instance, throughout generations, I’ve seen a seesaw of using fresh mushrooms and nondairy creamer to using cream of mushroom soup.”

Kelly Marshall

Wilkinson also wants readers to know the significance of sharing recipes from a “non-recipe” lens. This means using your own creativity and tastes to adjust family recipes to your liking. For instance, Wilkinson, who spent 20 years as a vegetarian, includes several recipes in her memoir like the Mess O Meatless Greens to show how many traditionally Appalachian dishes can be made without meat and taste just as good.

“It’s more than okay to do this with family recipes,” she says. “You’re still honoring your ancestors and solidifying yourself as a future kitchen ghost, too.”

Adding a personal flair and adjusting recipes to meet nutritional needs is how family recipes evolve, Wilkinson says. But it doesn’t mean that the history of the dish should be sacrificed. Oral storytelling, in particular, has been integral in preserving African American and African diasporic recipes for centuries.

While Wilkinson was able to gain a fairly solid understanding of her own family’s culinary journey through writing this book, she wants readers to know that even if you can’t piece together your past, there’s always room to create new traditions.

“Find old recipes and if they aren’t recorded, please write them down,” she says. “Ask your aunties, grannies, uncles, cousins, friends, and neighbors to share.”

Kelly Marshall

Photographs are also very important to preserving food histories. In collecting images for the book, Wilkinson was given lots of portraits from neighbors and friends who witnessed her family’s joy of cooking. “Don’t be shy. Snap photos of yourself, your children, the elders,” she says.

Aside from a wide array of delicious Affrilachian dishes, Wilkinson delivers an enlightening lyrical discovery of her foremothers, or those titular kitchen ghosts.

“This book is about the ways in which the foodways of the hills were passed primarily down through the women in my family, to me,” she says, “and how I will pass them on to future generations.”